Step-by-Step Guide: Planning an Argument Unit

ThinkCERCA teacher Maggie Verdoia walks us through her argumentation unit.

Argumentation isn’t just a unit. It’s a necessary skill for our students to be successful in the 21st century.

It’s also, however, a complicated topic. So when I teach my middle schoolers about argumentation, I make sure to incorporate activities that help them understand its many perspectives: such as how to spot the author’s claim, how to form a counterargument, how to engage in a debate, and how to evaluate evidence.

I’ve outlined my argumentation unit below, which I use for a sixth grade class but which can be adapted to fit any grade level.

With technology, our students have bountiful access to ideas and opinions. More than ever, it’s imperative to teach them how to analyze arguments and assess its legitimacy.

The Argumentation Unit Guide

Step 1 (one class period)

Warm up students’ argument brains by playing a game. I’ve used this one in the past:

- Pair students up—one student acts as the director while the other is the speaker.

- Assign a topic (e.g. camping) to each student pair.

- At “go,” the director says “for” or “against” to the speaker and the speaker has to come up with reasons either for or against the topic; the director continuously says “for”; or “against” so the speaker has to flip flop and practice coming up with reasons for each side. (This piece lasts about 30 seconds.)

- Change topics (some suggestions: smartphones, rain, fast food, watching TV, etc.) and students switch roles (again, about 30 seconds per topic).

At the very end, call student pairs up to the front of the room to demonstrate for the class excellent reasons for/against a topic.

Step 2 (two or three class periods)

Jump into the text.

- Start by using commercials and PSAs to introduce the idea of claims to students. (You could also use song lyrics!)

- Watch several, and work together to identify what the author wants the viewers to be “for” or “against.”

- Then, introduce the word “claim.” In 6th grade, we frame the claim as a should/should not statement.

Step 3 (two class periods)

Make the text more complex by asking students to read a newspaper or magazine article.

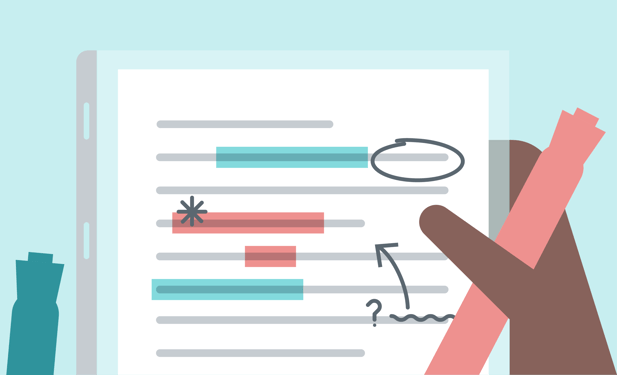

- The articles are placed inside a sheet protector and students use two different colored dry erase markers to mark up the text.

- Write the “for” and “against” claims on the board (again, phrased as should/should not statements).

- Ask students to highlight evidence in the text that proves the “for” and “against” side, using different colored dry erase markers. Students work in groups to identify the pieces of evidence that best prove both claims.

- Share findings as a class, correcting misunderstandings.

- Repeat this process 2-3 times, depending on the needs of the class.

Step 4 (two class periods)

Evolve on Step 3 by having students create their own claims.

- Students read paper-based articles, highlighting in different colors, and identifying evidence.

- Then, they work in groups to identify claims and supporting evidence.

Students are still working on identifying both sides of the argument. Often, students try to create claims using evidence from the text, so there’s a need for instruction around what a claim sounds like (again, should/should not statements) and how the evidence elevates it.

Step 5 (one class period per article)

Move into ThinkCERCA!

I use ThinkCERCA’s Curriculum to assign a level-appropriate text for each student. The platform’s writing supports help students form an evidence-backed claim in response to a writing prompt.

- Differentiate articles for students (typically 3 groups per class), so they’re reading about the same topic, but at appropriate grade levels. (I want my students to practice writing claims, evidence, and reasoning for less complex text so that they understand the procedure, and I then increase the text complexity.)

- Create a Google Slides presentation and lead students through each step of the CERCA process.

- Students are responsible for reading the article, making a connection, taking the comprehension quiz (which generates valuable data on their informational text comprehension), highlighting according to the prompts, and creating a claim. This is the first time that students are choosing a side of the argument; prior to this, they were exploring both sides.

- Review each student’s claim and made sure it answered the Class Discussion Question, did not include personal pronouns, and was broad enough to be supported by evidence.

Step 6 (one class period per article)

- Differentiate the next article for students and have them complete steps 1-3 of ThinkCERCA’s Writing Lesson (1. Connect with the text; 2. Read the text and answer questions; 3. Engage with the text by highlighting arguments).

- Check students’ comprehension.

- Then, ask students to create a claim (independently) and identify two pieces of evidence that prove the claim. Students are responsible for quoting and citing correctly.

Step 7 (two class periods)

Reasoning is the most difficult piece of the CERCA process for students. Most students try to restate the evidence or just say, “This proves that ...” Work 1:1 with students to get them to explain why the evidence they picked is the best to prove the claim, and type while they explain. Typically the reasoning emerges in this scaffolding process. I also use student exemplars to guide them.

- In this step, students are independently engaging in Steps 1, 2, 3, and 5 of ThinkCERCA (connect; read; engage; and build an argument). Students write a claim, and add two pieces each of evidence and reasoning.

- Then, before the next class period, go into ThinkCERCA, offer them feedback, and send their writing back.

- Spend at least one class period revising according to teacher feedback.

I’ve noticed that when my kids use ThinkCERCA, the skills of identifying evidence and writing reasoning to justify an argument end up transferring into other parts of my class.

While students were in literature circles, one group was having a particularly heated debate about a character’s motivation in A Wrinkle in Time. One student told me, “I keep telling my group members to justify their evidence using reasoning! See, ThinkCERCA is helping us!”

Step 8

In the last step, my students take their CERER (a schoolwide acronym to describe the claim–evidence–reasoning–evidence–reasoning structure) and flush it out into a full-blown body paragraph for an argument essay. Since they’ve already done the majority of the hard work, we only have to add a context and a summary sentence for each body paragraph. The order becomes: claim, context, evidence, reasoning, summary.

And that’s it! At this point, my students have gained a deep level of comprehension when it comes to argumentation, and are well-equipped to analyze claims and respond to them with appropriate evidence, reasoning, and language.

Maggie Verdoia is a sixth grade English Language Arts teacher at Raymond J. Fisher Middle School in Los Gatos, CA. She is a graduate of Gettysburg College and the University of California, Davis.