Project Ideas for Teaching Current Events and Critical Thinking

Today, just about anyone can share information. This has democratized news to the point where media organizations are no longer the sole gatekeepers of information. While this comes with many perks, it also means that not all information is reliable... after all, anyone can post it.

Renee, a teacher at Bowdon Middle School in Georgia, is not alone in worrying about the flood of news, opinions, and ads that today's students wade through online. A Stanford study found that more than 80% of middle-schoolers couldn't discern an advertisement from a real article.

"These are our leaders of tomorrow," Bowdon's Assistant Principal Kiley Thompson said. "And if we can’t teach them how to manage with the topics of today, what’s going to happen tomorrow? They have to be able to think about different perspectives and hear them and respond in ways that are appropriate."

With so much information accessible in an instant, today's students need critical thinking skills to:

- Interpret what they see

- Consider alternate viewpoints

- Seek sound evidence

- Make informed decisions

Empowering the next generation to engage civically, combat problems, and achieve success starts with ensuring they can think critically.

So when it comes to building critical thinking skills in the classroom, Renee and her colleagues are up to the task: They recently used current events – such as protests in the NFL – to spark courageous, collaborative, and critical discussions among students.

Here's how the Bowdon Middle School team helped students think critically about current events, along with two additional activities to help students make sense of the news:

Get the Resource Packet

Enter your email and we'll send you resources to use with the activities detailed on this post, including:

- A graphic organizer to help students respond to pro and con statements

- A template for writing persuasive letters to government officials

- A checklist to help students identify a native advertisement

Activity 1: Chalk Talk

Have students respond to statements on current events – and to their peers' anonymous viewpoints.

At Bowdon Middle School, the first period of the day is devoted to literacy, and groups are differentiated by level. To get students talking about current events in a productive manner, teachers recently introduced a spin on the traditional chalk talk activity to spur classroom discussion.

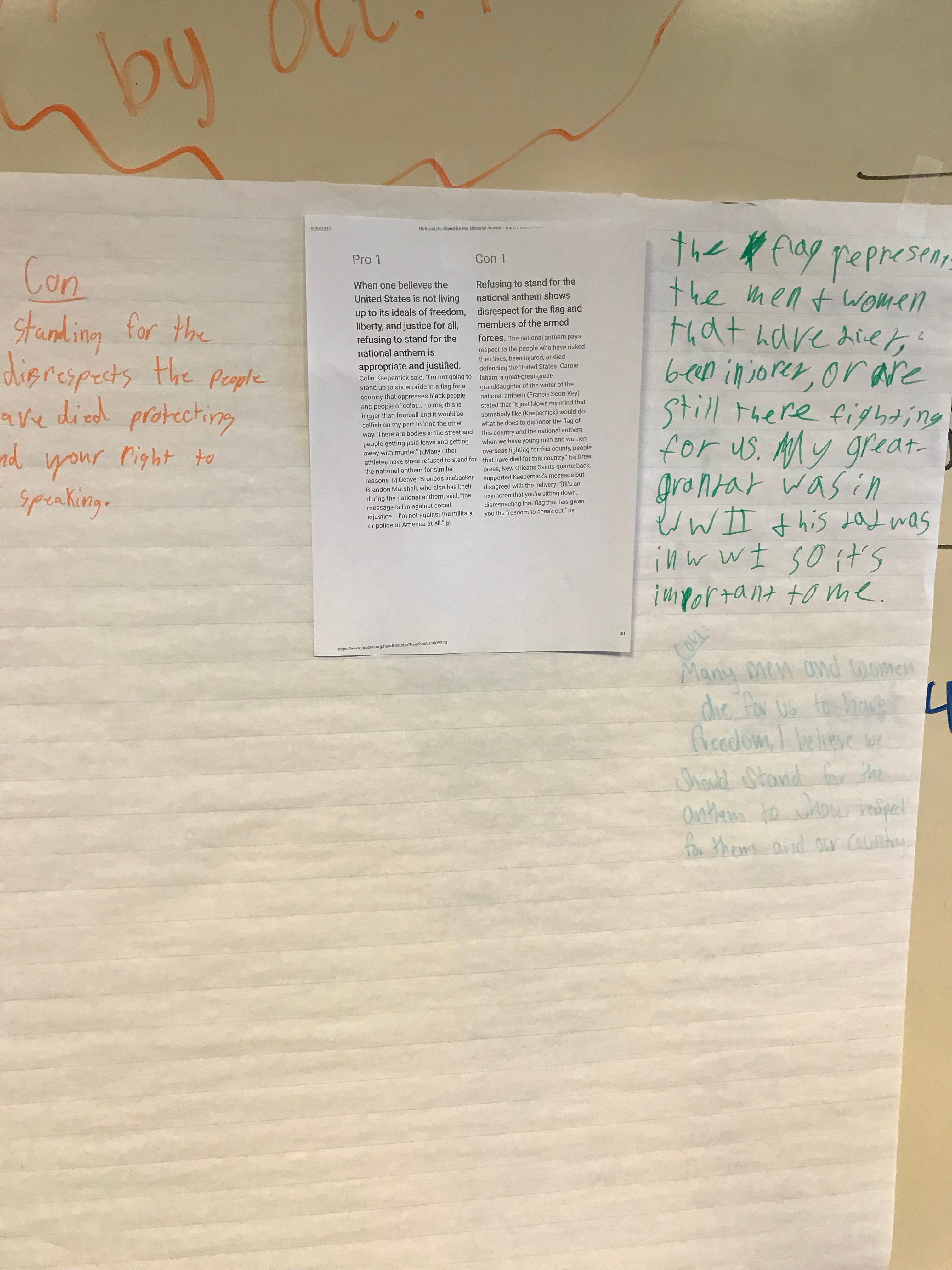

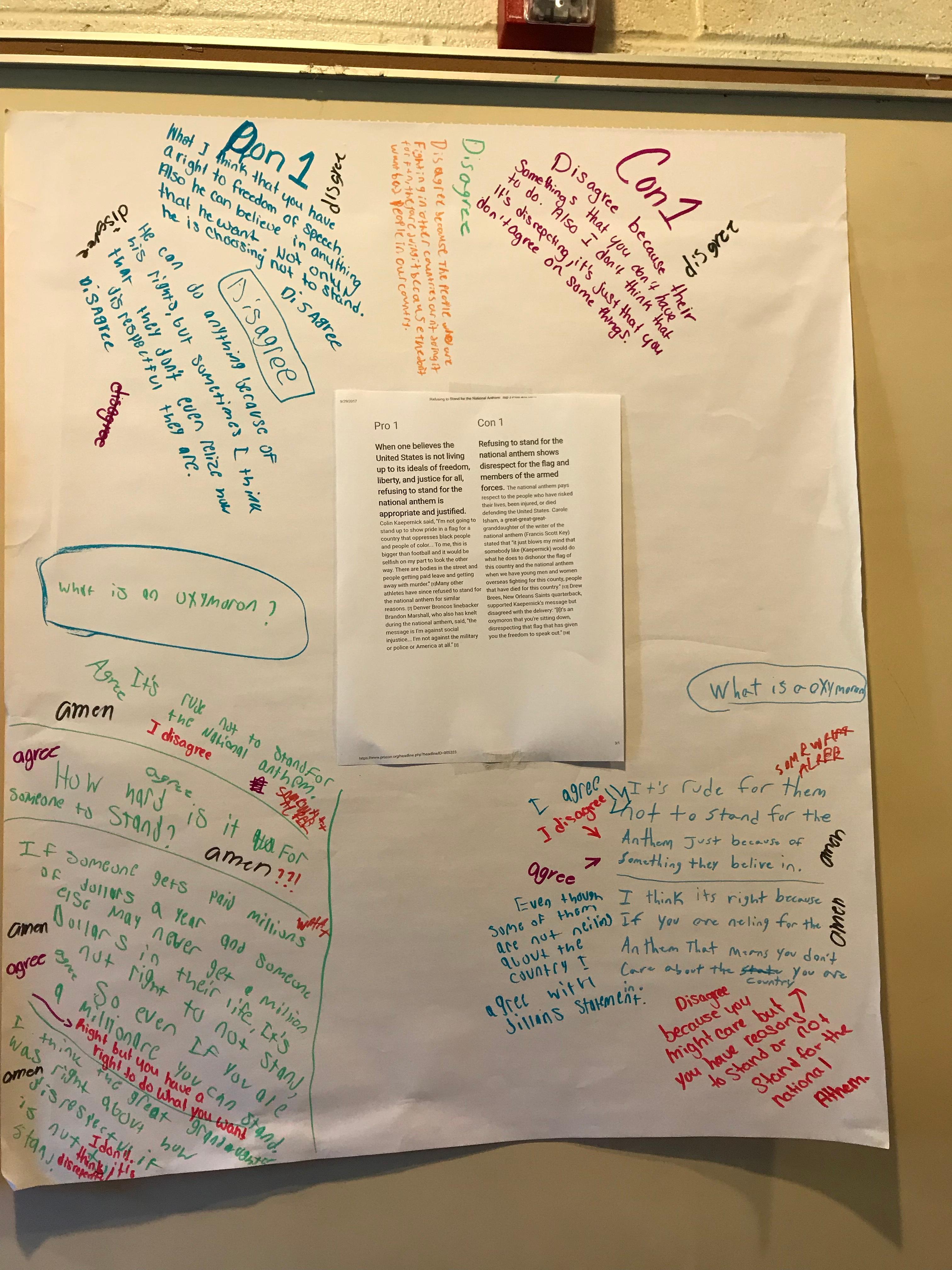

For this activity, teachers pasted pro and con statements from leveled articles to posters on the classroom walls. They asked students to silently – and anonymously – read both sides of the argument and leave a response.

After students left responses, the Bowdown teachers then asked them to read their peers' viewpoints and respond to those as well.

"It really got students to a deeper level of thinking – like, okay, this is what’s going on," said Bowdon Teacher Jennia Hendrix, who used the strategy with her students to discuss protests in the NFL.

"I think it helped them understand both sides of the argument," Bowdon Teacher Michelle Frazier added. "That way they’re not only seeing one side, maybe what they hear at home or what they hear on the television. They’re focused on both sides of the story."

At the start of the activity, Bowdon teacher Kelly Ogles noted, students were hesitant to write. But in a discussion that might normally be dominated by the loudest or most passionate voices in the classroom, the Bowdon teachers found that the act of writing down responses prompted students to really think about the issue – rather than jump to an immediate conclusion.

"There’s a level of thought that goes into putting something down on paper... it is a little more thoughtful than just snapping off some comment," Assistant Principal Thompson noted. "That’s what I think the benefit of teaching strategies like this and actually performing them in the classroom is: Giving [students] the opportunity to experience conflict where there’s not an immediate response."

By teaching students to think, interpret, and respond beyond reaction, Bowdon teachers can ensure that their students attain the skills necessary to navigate the world of social media – which often heaps praise upon black-and-white interpretations of complicated issues.

To replicate Bowdon Middle School's version of the Chalk Talk in your classroom, whether it is in-person or virtual, follow these steps:

- Search for articles about a current issue from relevant, reliable resources with a track record of strong reporting.

- Print out, cut, and paste arguments to various posters and hang these on the classroom walls if you are in a traditional learning environment. The arguments should be clear and include some context. If you are in a virtual classroom, you can post arguments in a shared document or drive that all students can access.

- Read the article(s) aloud with students or ask them to read silently.

- Talk about viewpoints regarding the current issue with your students. Consider playing devil's advocate if most of the class seems to agree with one viewpoint, as students might be nervous to advocate a less popular position, or might not have fully considered both sides of the argument.

- Ask students to think, and then respond with a full sentence to the pro and con statements on the posters. Ask them to do so silently and anonymously. If you are in a virtual classroom setting, you can use a form or another paired platform that permits anonymity.

- Next, tell students to read their peers' statements and respond to them with evidence-based statements. Again, ask students to do so silently and anonymously.

- Then, engage students in a full-class discussion on the topic, or introduce an argumentative writing project about the topic.

Activity 2: Persuasive Letter Writing

Help students write to their representatives about an issue in their community.

Though many students may not yet be able to vote, they can still make their voices heard on matters they care about.

By writing persuasive letters to representatives, students take critical thinking a step further – they turn their thoughts into actions and attempt to solve a problem by using their voice. Students can write a letter to their mayor, their senator, or even the president.

A ThinkCERCA 8th-grade classroom recently did just this. Students consumed news that covered the murder of Ahmaud Arbery. They discussed the case as a class and were each prompted to respond by writing a persuasive letter to government officials in Georgia, the state where Arbery was killed, demanding that his murderers be charged and prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

Use the following template to help your students write a persuasive letter to their representative. (Fill out the green form above to download this template as a PDF).

How to Write a Persuasive Letter to a Representative

Audience: The audience for this letter is specific – it's one individual. Think about the recipient's values, statements and actions when writing the letter. It will help you to appeal more to him or her.

Dear [representative]:

I am a [descriptor] from [location]. [Topic] is very important to me because [personal connection].

Evidence and Reasoning: Start with a surprising or powerful piece of evidence to grab your reader’s attention.

In fact, [topic] affects [number] people in [community] right now by __________, which demonstrates __________.

Or:

In fact, studies by [reputable source #1] and [reputable source #2] show that [topic] will [cause some action], which demonstrates __________.

Claim and Reason: Then, connect your evidence and reasoning to your central claim.

As our representative, it is important for you to __________ so that __________.

I humbly propose that you respond to this issue by [suggested action]. This action will __________ because __________.

Counterargument: In a letter to a government official, you could refer to a position another official has taken or another public position that has been taken by others recently.

While [a different representative or group] has [taken a different action] instead, I do not think you should pursue that action, because __________.

Conclusion: Again, considering the Audience of the letter, conclude your letter by appealing to the reader to take action based on your claim.

Considering all this, I hope you act on this community issue and [proposed action].

Sincerely,

[Name]

This template follows the CERCA framework for argumentative writing. Learn more about CERCA >>

Activity 3: Decipher the News

Show students how to analyze news articles.

“Fake news” is not just a hot topic. It’s a real problem. And given the instant accessibility of information online, people are susceptible to automatically believing what they see on their phones.

It’s therefore imperative that we train students to think critically about what they see posted, shared, and upvoted on the internet. They need to know how to spot the difference between real news and an advertisement, to verify a source's evidence, and to catch when an author displays bias.

To help your students think critically about articles, images, and videos they see, incorporate these strategies into a lesson:

Spot Media Bias

- Find 2-3 articles that cover the same topic, but which target different audiences (perhaps by location, occupation, age, or political affiliation).

- Get paper copies of these articles, but remove identifying information – such as the article source, author, or even distinctive styling. If you are in a remote learning environment, you can copy and paste the articles into one shared document. You can make the source and author not visible for your students and can edit the font and format of each article to match so that any identifying information is eliminated.

- Ask students to read an article, and write down their impression of the topic based solely on the information contained in that article (if they are already familiar with the topic, ask students to ignore prior conceptions for the time being).

- Repeat step 3 for each of the articles.

- If the articles target different audiences, the impressions left by topics will probably be skewed to align with the beliefs of each audience. Ask students to highlight words or phrases in the articles that lead them to a particular impression about the topic.

- Then, as a group, discuss how the lens through which information is presented can impact its perception. Talk to students about why these differences arise, and about whether bias impacts a story's credibility.

[Read more: Media Bias: What It Is and How to Spot It]

Track Evidence

- Give students an article to read online. The article can be on any topic, but scientific articles (such as from National Geographic) work particularly well for this strategy. The following steps are compatible with in-person, remote, and hybrid learning environments.

- Ask students to mark every single fact from the article. This could include titles, statistics, names, dates, and assertions of something that did happen or could happen.

- Then, ask students to verify everything the author stated. If the article talks about research, ask students to read the research. How can they be sure that the evidence an article links to is accurate? Challenge students to find the primary source for each statement referenced in the article.

- Finally, bring the class together for a conversation. What facts or statements were students able to prove? Did they find any errors? Do they have any doubts about the accuracy of certain statements? Could the author have missed something?

By challenging students to evaluate evidence, they'll learn to not always accept the presence of links as verification. Anyone can link to a study or provide seemingly-factual footnotes. Trustworthy articles must base their statements on trustworthy facts.

[Read more: When Articles Link to Evidence, How do We Know the Evidence is Accurate?]

Spot an Advertisement

Native advertising, or the style of promotion that blends paid media into the content it is embedded in, is on the rise – and it's blurring the line between what's objective and what's paid for online. Native advertisements do not look like ads and are intended to blend into the user's native experience.

In fact, a recent study showed that more than 80% of middle schoolers could not tell the difference between an actual article and a sponsored advertisement. Since promoted posts cannot be unbiased – they are, by nature, intended to target customers and sell an idea or a product – students must recognize when a post is paid for, and whether it's intended to lead them to a specific conclusion or action.

To help students spot an advertisement:

- Find examples of native advertising online. These can be articles or even tweets or Instagram posts.

- Once you've found an example of native advertising, also grab examples of similar posts that are not advertisements. For instance, if you found a listicle that discloses that the publisher makes money off of links for the native advertisement example, choose a few non-promoted listicles from the same publisher for examples of editorially independent posts.

- Then, on a screen or on paper, present all the posts to students, side-by-side. Ask them to determine which posts are advertisements, and which are not. Challenge them to explain their reasoning and look for counterarguments.

[Read more: Real News and Sponsored Articles: Distinguish them with this Checklist]

Mallory Busch is ThinkCERCA's Editor of Content Strategy. A graduate of Northwestern University, Mallory came to ThinkCERCA from stops in audience strategy at TIME magazine and news applications development at Chicago Tribune and The Texas Tribune. She holds degrees in Journalism and International Studies, and was a student fellow at Knight Lab in college.